Self-portrait as Hohepa Te Umuroa

In 1770 Captain Cook landed on the east coast of Australia at Botany Bay where men were fishing from bark canoes. The Tahitians had greeted the Endeavour in elaborate outriggers, the Maori had performed haka and thrown stones. But these men were different. They ignored the English sailors who landed after firing a few shots which sent men on shore scurrying into nearby bush.

Cook left some beads in a humpy near the beach where children and women huddled. They refused to touch them. Cook wrote, “…We were never able to form a connection…They seemed to have no curiosity, no sense of material possessions…All they … want[ed] was for us to be gone.”[ii] For seventeen more years, no other English eye saw this land’s waters, rocks, or grey green gums, where for nearly 30,000 years, a ‘thin membrane of [Aboriginal] culture’[iii] had spread itself over the continent in an elaborate, but to the Western mind, utterly alien web of tribal and familial relationships.

Cook’s observations and Joseph Banks’s description of the geography of Botany Bay and native ‘cowardliness’ (compared with Maori bellicosity) persuaded Pitt’s Cabinet to establish a penal colony there, and in 1787 the First Fleet of over six hundred convicts sailed into Sydney Cove, under the rule of Captain Arthur Phillip, to turn this Spartan-like Eden into the world’s biggest prison.

But what about the incurious vanishing locals? They seemed so few; they hunted and gathered with spears and stone axes, lived in caves or under sheets of bark, wandered naked over the land in tribes; owned nothing, lacked any recognisable hierarchical structures. They were nomads indeed, unlike the land-hungry new arrivals for whom property was the basis of their coming. This land, to all intents and purposes, was ‘empty’. Thus, by 1835, the doctrine of ‘terra nullius’ – land belonging to no one – was established by Governor Bourke of NSW which determined that indigenous Australians could neither sell nor assign land, and that its distribution was the Crown’s prerogative. So the scene was set for whole-scale dispossession because one of the ‘rewards’ at the end of a convict’s sentence was the acquisition of his ‘own’ land. An ancient pre-existing culture of sung myth in which every tree, hill and animal were sacred – intimately bound to the peoples who walked among them in ‘dreaming-tracks’ – was inconceivable to the colonists. Restriction of movement over ancient tribal territory, confiscation of land, or relocation to different parts of the country meant inevitable spiritual death. This has ongoing consequences culminating in annual Invasion Day protests every Australia Day.

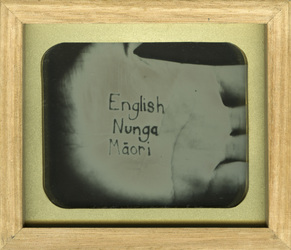

This is the historical backdrop of Adelaide-based photographic artist James Tylor, a descendant of the Kaurna people whose traditional lands include the Adelaide plains of South Australia. He is also an ‘Australian-Maori’ whose family moved to Australia in the 1930s. His father was ‘very much a Maori’, and James grew up as a ‘Maori boy’ which he pronounces with a colonial inflection because that was his experience and is his identity. And he has English forbears. He knows some ‘Nunga’ which he describes as a kind of ‘contemporary (Aboriginal) language from South Australia.’

His work captures both his examination of his own identity – Voyage of the Waka, the Origin of the Dreaming, and most recently Aotearoa my Hawaiki, and the chronicling of the erasure of indigenous sites and practices as a result of land clearances.

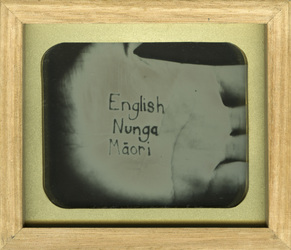

Self portrait, 2013 Daguerreotype from Voyage of the Waka

‘twinkling eyes of cunningness and ferocity’,2013 Daguerreotype.

In the Waka suite Tylor steals phrases from Darwin’s Voyage of the Beagle to illustrate the attitude of the white man towards the Other. He also makes himself the subject of some works. This deliberately unsettles the viewer’s assumptions about the nineteenth century predilection for taxonomy (and judgement), and whether or not it still prevails. As a self-portrait, the artist also meets himself – in the photograph of his face, he stares unflinchingly through the frame; and his tattooed, or branded, hand could either be reductive classification or affirmative personal statement. That this hand is open suggest acceptance of the blending of his three cultures.

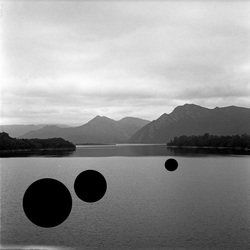

From an Untouched Landscape with its two categories: Deleted Scenes and Erased Scenes, Tylor questions European notions about the Australian landscape. Because so many indigenous people were removed from their lands and corralled into government reserves, and their artefacts razed in the settlers’ quest for land for forestry and farming, a perception – still maintained – has developed that the Australian landscape was always ‘untouched.’

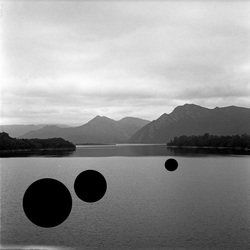

In a series of quietly devastating photographs Tylor has cut dark voids into landscapes that were once significant cultural sites and backed them with velvet. Some voids are tomb-like, their implacable blackness denying forever the possibility of return, others are circles which ripple away into the distance suggesting an ongoing history of loss.

(Erased) From an Untouched Landscape #7, 2014, Inkjet print on hahnemuhle paper with hole removed to a black velvet void.

(Deleted scenes) From an untouched landscape#6,2013, Inkjet print on hahnemuhle paper with hole removed to a black velvet void.

Un-resettling continues to question absence. Although environment and heritage organisations respect significant Aboriginal sites and acknowledges traditional ownership, it is illegal to remove objects or disturb the landscape. Tylor believes that this restriction prevents indigenous people from hunting, gathering or building structures in public reserves. Un-resettling is a series of photographs in national parks where he has erected dwellings to show that they once existed as part of the landscape. The absence of people in these images emphasises the practice of relocation and dispossession.

Un-resettling (half dome hut on desert plain)2013, Handcoloured Digital Print.

When James was studying in Tasmania in 2012 he heard about gravestones on Maria Island – off the coast of Tasmania – where the words were in Maori. Until then he’d always believed that penal settlements in Van Diemen’s Land were for white convicts only. Research led him to Te Umuroa and six Whanganui Maori who had attacked a farm in the Hutt Valley in 1846, and under George Grey’s orders, were subjected wrongly to a court martial. The men spoke insufficient English, their interpreter was inadequate and they were denied legal counsel. They pleaded guilty. Their crime was ‘rebellion against the Queen and possession of one of Her Majesty’s firearms.’ They were sentenced to be ‘transported as Felons for the Term of their Natural lives’, banished from their own island and incarcerated on another.

Displaced Rebellion is a series of self-portraits in which he represents himself as Maori who were sent to Van Diemen’s Land. As an Australian of Maori descent, Tylor acknowledges the significance of their story to his own historical connection to Australia.

Self-portrait as Te Kumete, 2013.

His most recent work is an investigation of his mythological origins. Names are important to him for what they reveal about identity and culture, and this series is entitled Aotearoa, My Hawaiki. ‘There’s always a place where your ancestors come from. I prefer to call mine Aotearoa for what it means – New Zealand is just a Dutch label.’ It is fourteen black and white disarmingly serene invocations to the clouds which hover over landscape and acknowledge the significance of Aotearoa. The bottom third of each image, however, is dark and unknowable, and slicing through the darkness is a tear, a separation between land and sky. ‘Ripping the landscape is,’ he says, ‘about not having a connection to these places – about displacement brought about by colonisation. Most of my work is about my mixed race and heritage – this is the first time I’ve really thought about being a Maori-Australian.’

Aotearoa my Hawaiki #11 2015,Inkjet print on hahnemuhle paper.

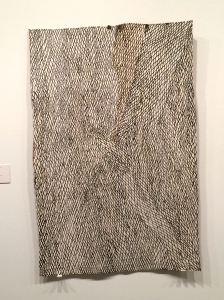

James Tylor’s work is meticulous, considered, and beautiful. Because his practice is grounded in history, he works with historical photographical processes from the 19th century especially those used to document Aboriginal and Maori culture. Before he studied photography, he was a carpenter and a coexistent part of his art is the making of hybrid artefacts: in Past the Measuring Stick, 2013, he makes a kauri boomerang, a manuka gidgee, a harakeke dilly bag.

Tasmanian blackwood patu. 2012. Ambrotype on black glass with clear glass mounting.

James Tylor is currently walking around Kangaroo Island, the third largest island in Australia after Tasmania and Melville Island, and once a border of Kaurna territory – their name for it was Karta, or Island of the Dead. When it gets cooler, he plans another longer walk along Kaurna borders – from Cape Jervis to Port Pirie – and he wants to learn more of their language. ‘You have to be in a place to understand its history and you want to speak words rather than decipher.’

In June, July and August, his work will be shown in Some Australian Photographs at the McNamara Gallery in Whanganui. His website is Jamestylor.com

This essay first appeared in ArtZone 58 2015.

[i] http://www.captcook-ne.co.uk/ccne/timeline/voyage1.htm, Joseph Banks recorded the fishing party observed at Botany Bay on 26 April 1770. He wrote: ‘Their canoes… a piece of Bark tied together in Pleats at the ends and kept extended in the middle by small bows of wood was the whole embarkation, which carried one or two…people…paddling with paddles about 18 inches long, one of which they held in either hand. (Banks, Journal II, 134) retrieved 10 Feb 2015

[ii] Hughes, Robert, The Fatal Shore, London, Pan 1987, chapter 3, p59

[iii] Hughes, Robert, op cit, chapter 1, p9